Invertebrates

What are freshwater invertebrates and why do we care about them?

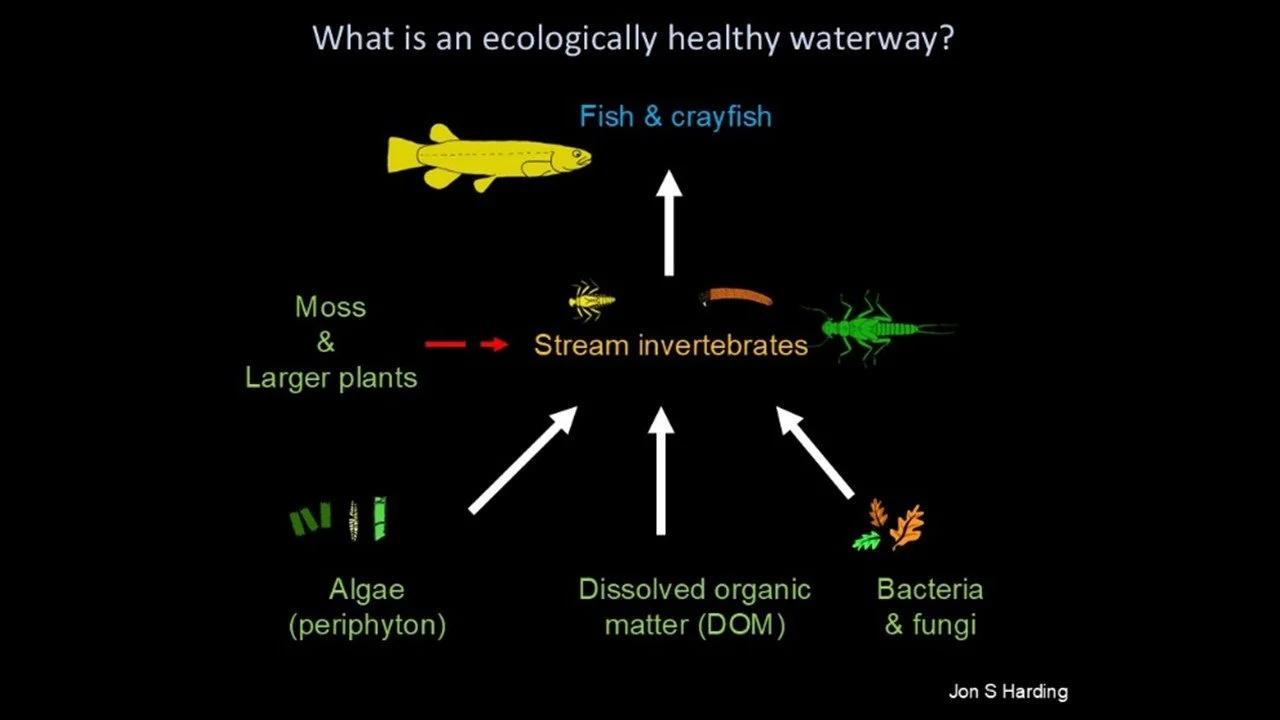

One important aim of the Styx Living Laboratory Trust is to “support a viable, healthy spring-fed ecosystem”. A river ecosystem that’s viable will have a healthy freshwater food web.

This food web needs to have “food” for animals living in and around the river (i.e., invertebrates, fish & birds). This food will include of bacteria, fungi (on decomposing leaves & wood) and algae. Rivers will also typically have mosses, lichens and large aquatic plants (macropytes). However, these last three are not eaten much by New Zealand freshwater animals.

The main consumers of this food are freshwater (or stream) invertebrates. An invertebrate is a small animal that does not have bones. To name a few, they include insects, snails, worms, and tiny zooplankton.

Typical healthy stream foodweb

Freshwater invertebrates are everywhere in our river! They are great indicators of the health of our river. Some invertebrate species are wiped out by pollution, while other species can live in polluted waters. So, understanding what invertebrate species we have tells us a lot about how polluted our river is. On top of this, the invertebrates live most of their lives in the river. As a result, they tell us how polluted our river is over the longer-term (e.g. 12 months or so), compared to water quality monitoring which only provides data on what the water quality is like at that specific time.

Examples of some freshwater invertebrates in thePūharakekenui/Styx River (a mayfly, some cased caddisflies & a backswimmer).

In a healthy food web, invertebrates are eaten by larger animals such as crayfish, fish and birds.

Examples of predators in the Styx River

How do we use invertebrates to tell the health of our river?

We use two methods to find out what species we have at a site in the river:

We sample the bed of the river using a net to catch invertebrates. We then identify these animals. Typically, this is done under a microscope in a laboratory.

More recently we have been collecting environmental DNA (eDNA). This involves collecting a water sample (over 12hrs+) and sending the sample to a lab to test for DNA fragments of all the animals that are in that sample.

For both methods, we end up with a list of species. We use this species list to calculate several measures (biotic metrics) that tell us how healthy our site is.

Kick-net & eDNA sampling for freshwater invertebrates

If you want to find out more about invertebrates have a look at these videos:

A beginner’s introduction to freshwater benthic invertebrates

Beginners guide to New Zealand lake and wetland invertebrates

Identifying benthic stream invertebrates to Order

Keen to get involved and learn how to monitor freshwater invertebrates in the Pūharakekenui? Come along to one of our invertebrate monitoring days! Click here for more information!