Vegetation

Understanding the Past

To understand the long term vision for vegetation in the catchment, especially that associated with the green corridors along the waterways and wetlands in the catchment, it is important to appreciate the past. There have been three distinct phases associated with vegetation in the Pūharakekenui/Styx catchment. The first stage can be described as natural,/pre-human, the second stage induced native/polynesian and the third stage induced exotic/European.

The natural vegetation prior to human occupation consisted of a range of vegetation types based on soil moisture regimes, soil types and the effects of natural disturbance. The different vegetation types can be described as:

wet forest dominated by kahikatea

dry forest dominated by totara

saltmarsh at the river mouth

mire wetlands

riparian river margins

submerged river aquatics

savannah on dryland sites

coastal sand dunes

successional forest and shrubland following disturbance.

The successional forest would have been dominated by manuka and/or kanuka, and would have been a temporary occupant of the site following incursions of the Waimakariri River, severe storm events, and other natural disturbances.

Polynesian occupation resulted in modification of much of the Canterbury Plains through burning. This lead to an increase in successional vegetation types and a reduction in forest as can be seen in the ‘Black Map’ with the dominance of fire-induced vegetation comprising of:

tutu and bracken

swamp wetlands of raupo and flax

open grassland

shrubland

The process was taken further following European occupation with the intensity of modification, farming and the introduction of an alien flora and both domestic and feral livestock. The original vegetation has all but gone, resulting in the following:

pasture grasslands

exotic pine forest

swamp wetlands

exotic scrub

willow riparian margins

marram sand dunes and dune migration

urban development

Reversing the Trend

There is clearly no opportunity for a natural return to anything resembling the original vegetation due to impacts of urbanisation and private ownership. To regain what has been lost, two actions need to be undertaken, these are firstly, ‘protect’ and secondly, ‘restore’.

The first task is to identify and protect those fragments that remain through appropriate management. Fragments that still existed in the Pūharakekenui/Styx catchment in 1993 were identified by Meurk et al. with those sites considered of greatest value being protected as Ecological Heritage Sites in the Christchurch City Plan. As part of the Belfast Area Plan, many of these sites were re-surveyed in 2007. This showed that many sites in the catchment had not had adequate protection, and declined even further. Some sites had been lost altogether.

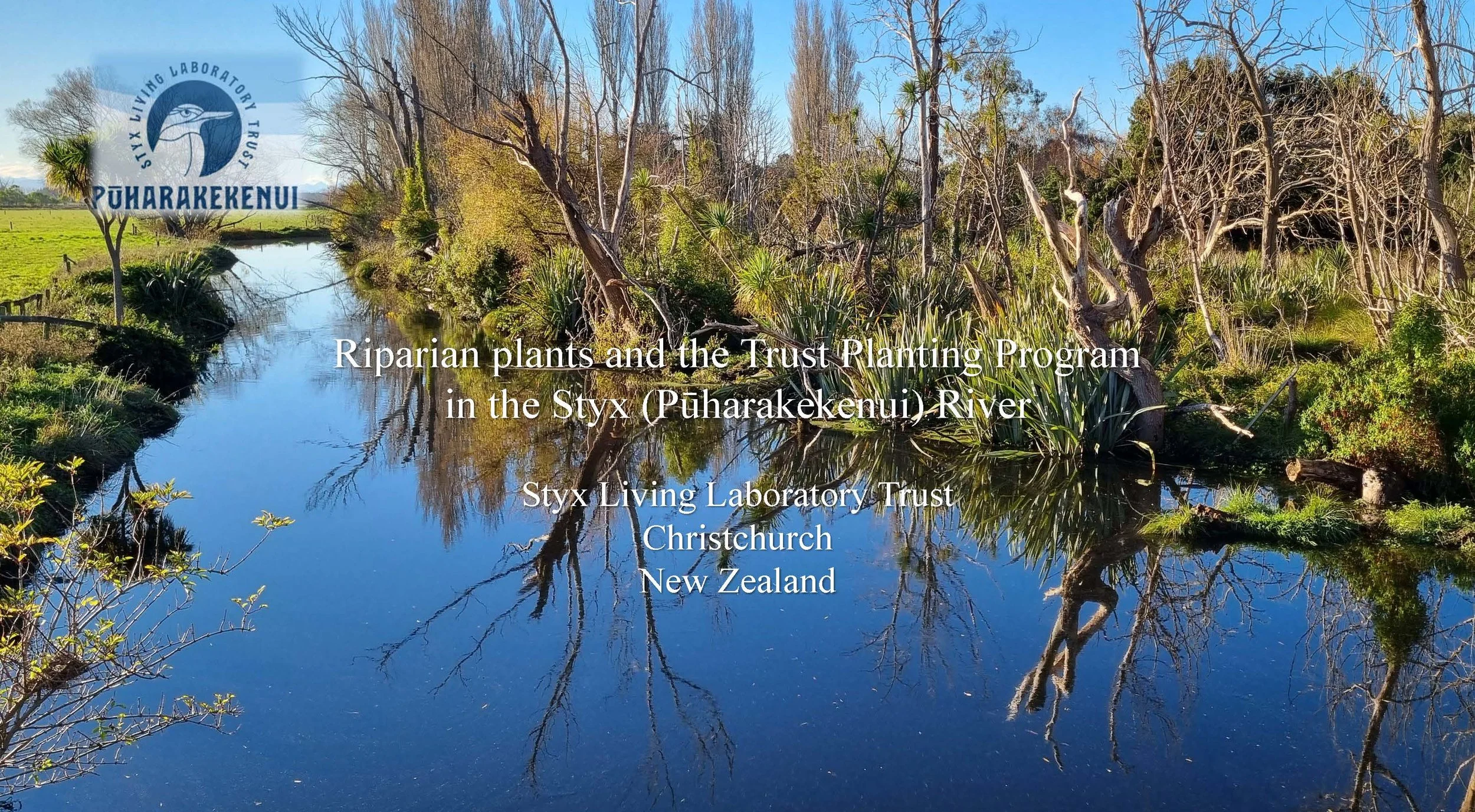

The second action is to restore what has been lost. This will require creating many habitats from scratch as there is very little indigenous vegetation remaining. It can be a difficult task and requires careful research and planning, plus a degree of experimentation. The obvious starting point, and probably the most straightforward system to restore, are the riparian margins of the Pūharakekenui/Styx River, itself. This will involve the conversion of willow forest back to indigenous riparian margins of sedges, rushes and ferns with adjacent forests and shrublands. For other habitats the task may be harder, and in some cases potentially impossible. Larger core areas of wetland and dryland forest can be developed at specific sites along waterway corridors where opportunities exist. It is however, very difficult to create wetlands based on peat-based mire systems such as fens and bogs due to the underlying soil and water conditions that are required. To date, created wetlands around Christchurch are limited to swamps on a mineral substrate. The true dryland ecosystems such as savannah, may also present a difficult challenge.

Taking a pragmatic approach with the knowledge available, the following is a vision for the future vegetation of the Pūharakekenui/Styx catchment. This approach links back to the original vegetation types.

(i) Riparian corridor

Restored forest/riparian river corridor with associated core forest areas.

The result is a major ecological gain.

(ii) Wetlands

Restored swamp wetlands with well-protected mire fragments as fens.

(iii) Forest

Core areas of restored forest.

When Europeans arrived in Christchurch only two remnants of the original forest remained, and of these only Riccarton Bush survives today.

(iv) Dryland Savannah

The Pūharakekenui/Styx catchment probably contained very little of this, although there would have been extensive areas to the west of the catchment. Most of the restoration opportunities have gone, but there are a few small areas with sufficiently droughty stony soils that might allow for the restoration of savannah vegetation. Such a restoration has not been undertaken anywhere in New Zealand, and attempts in Christchurch to re-establish the woody component have largely failed.

(v) Saltmarsh

As the least-disturbed vegetation, this is likely to be the most successful. The mouth of the Pūharakekenui/Styx River and Brooklands Lagoon retain good areas of salt marsh. The area immediately upstream of the Pūharakekenui/Styx River mouth has however, been extensively modified by structures associated with river protection and land drainage activities within the river itself. Never-the-less, there may be some opportunities to restore the salt marsh in these areas.