Riparian Vegetation

Riparian vegetation is the term used to describe plants living or located on the bank of a natural course of water, such as a river or stream.

This bank area, known as the riparian zone, provides an interactive link between the surrounding land and the aquatic system.

Why measure riparian vegetation?

Because an interactive connection exists between the surrounding land and the aquatic system, the types of plants that grow in a riparian zone are known to have a major influence on the ecosystem of the waterway.

Examples of this include:

- Overhanging and semi-aquatic vegetation offer cover protection for fish and invertebrates. Additionally this vegetation provides a food source for aquatic animals, both from the plant material itself, and from insects that may fall off foliage into the water.

- Vegetation growing on the verge of the river offers spawning sites for smaller fish, such as inanga (whitebait).

- Riparian plants act as habitat, cover and a food source for the adult terrestrial stage of aquatic insects.

- Trees that shade a stream help to keep water temperatures lower.

- Roots of trees and other vegetation assist in consolidating and stabilising stream banks.

- Exposed roots and woody debris in the water provide shelter for fish, and additional habitat for invertebrates.

Given that riparian vegetation has considerable impact on waterway ecosystems, it is important to monitor the changes that occur over time.

Riparian vegetation is determined visually by inspecting and recording percentages of types of plants within a given area.

- Determine the upper bank and lower bank areas using the following diagram to assist in deciding their location. The crossover point between upper and lower banks is located where a significant change in predominant bank angles occurs. This point may not always be as obvious as shown below but by ignoring small differences and concentrating on the predominant angles the crossover point should become obvious.

- Assess and record the various types of riparian vegetation present in the upper bank area.

The list on this page provides a description of the various Categories of Vegetation that are likely to be encountered.

As the purpose of collecting data is to observe changes in riparian vegetation, it is important to ensure that the exact same site is used on each occasion monitoring takes place. This can be done by either using a GPS unit to ensure accuracy of location or by comparing photographs of landmarks taken on earlier monitoring visits.

- Determine the boundary of the upper bank area that extends 5 metres back from the cross over point.

1 being equal to less that 10% cover,

2 equalling 10 to 50% cover, and

3 equalling over 50% cover

- Repeat this process to assess and record the riparian vegetation present in the lower bank area.

Vegetation

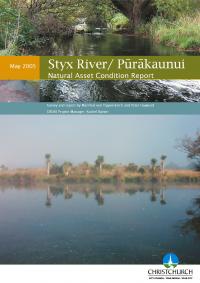

An illustration showing the Pūharakekenui in a natural state. The riparian zone is only around the banks of the river itself, although activities called riparian restoration often involves planting on higher areas along the river banks as well to deliver the best results. Image from Meurk, C (2004). Vegetation & Landscape Potential, Styx River Catchment, Christchurch. Christchurch City Council.

History of Riparian Vegetation along the Pūharakekenui / Styx River

The riparian zone is the narrow band along the edge of rivers, ponds, and swamps. Here the damp ground, occasionally underwater, creates a unique community. Before human arrival the Pūharakekenui was primarily towering podocarp swamp forest, dominated by totara, matai, and kahikatea. Totara logs from this early era still lie buried under parts of the Pūharakekenui.

Under pre-European Māori governance, the Pūharakekenui encompassed huge wetlands dominated by smaller riparian plants like flaxes. A southern trade route ran through the area, and there were many settlements along the river. The riparian zone was important for mahinga kai (obtaining food

and resources). Plants cultivated in and gathered from the riparian zone included harakeke (flax) for weaving and its edible flower stalk, tī kōuka (cabbage trees) for their edible insides, and aruhe (bracken fern roots). The riparian vegetation was also home to many edible birds. As the European population in Christchurch grew, settlers drained the marshes to create farmland. European plants were also introduced. The most significant were the willows, which grow thickly in the riparian zone, replacing native vegetation with permanent willow forest. Riparian vegetation was less important to European settlers, although they did make some use of it. Harakeke was used the make ropes for ships: the “Mill” in “Styx Mill Reserve” may have originally been a flax mill.

The Riparian Vegetation Today

Levels of native vegetation coverage in the catchment today are low, ranging from 5% to 30%. The species that make up this cover, however, are very uneven. Due to significant replanting efforts, there is reasonable diversity of small trees, shrubs, native grasses, and flaxes. Podocarp trees like matai and kahikatea have also been replanted, but will take many decades to reach their full size. Among the smaller plants, diversity is much lower. There are often remnant species, a few resilient species who have survived through decades of upheaval. Species of ferns, sedges, and vines that are tolerant of disturbance remain, inhabiting areas where they have little direct competition. A few highly competitive native species, including cabbage trees and bracken fern, can establish around the Pūharakekenui on their own, especially in hedgerows and unused ground in the upper

catchment. There are very few small herb species left, due to the prevalence of taller and more aggressive weeds. One notable herb species is the swamp nettle (Urtica perconfusa), a vulnerable species which hangs on in a few patches in the river’s central reaches. All these native plants are

outnumbered by introduced species. The most prominent of these are still the willows, which form thick stands where very few native species manage to survive. Other riparian zones are covered by thick grass growth, and riparian weeds like monkey musk and yellow flag iris.

The Role of Riparian Vegetation

As well as having its own inherent value, well-developed riparian vegetation brings a wide range of ecological benefits to the riverbanks and the river itself. Riparian vegetation supports a diverse range of native animals by providing habitat, food, and movement corridors. Tussocks provide shelter and nesting sites for waterfowl, while trees provide space for many other birds. Riparian vegetation often involves a lot of different heights and growth forms, which creates many different habitats and so is capable of supporting higher species diversity. Plants like pohuehue are excellent food for native caterpillars. Trees, including kowhai, kahikatea, totara, matai, broadleaf, and hinau, provide fruit and nectar for native birds and other animals. Having a wider variety of these plants creates food sources that are available for more of the year and less vulnerable to something happening to one food species. The many invertebrate species the plants support are also a food source in their own right. Riparian habitats are also vital movement corridors for animals. Urban areas often have

many small patches of native vegetation. But animals are often unwilling or unable to move long distances across space in between them, which they see as unsafe. This isolates the native patches, meaning the animals that live in them will eventually disappear. Corridors of native vegetation the

connect many native patches together help fix this problem, allowing for interconnected, sustainable animal populations. Rivers, which naturally cross wide areas, make ideal corridors if riparian vegetation is planted right along them. A well-developed native canopy even helps naturally

supress weeds, as most weed species require high light levels.

Riparian vegetation also helps the health of the river. Roots reduce erosion by locking together and stabilising soft soil, maintaining the stream banks and reducing sediment levels in the water. This helps stop sediment from being deposited on the riverbed, where it covers rocky habitat and

smothers away most of the native stream life. This is especially important in the Styx, which has a major sedimentation problem that has gotten dramatically worse in recent decades. Canopy cover over the river also reduces weeds in the river itself, not just on the banks. A riparian canopy also reduces the water temperature, by as much as 6°C. This is important as many of New Zealand’s aquatic invertebrates are adapted to cooler waterways and can’t survive in open streams in summer.

Riparian vegetation can filter pollutants out of rainwater, and even reduce flooding. Riparian vegetation acts like a sponge, slowing and containing high water flows. This reduces the amount of water building up in vulnerable areas at once, making floods less likely.

Riparian Restoration

Developing riparian vegetation all along the Pūharakekenui is the key to building a sustainable ecological community in this part of Christchurch. The past loss of vegetation along the river means this process has had to largely start from scratch. However, the Pūharakekenui is fortunate

compared to Christchurch’s other rivers because the riparian zone itself has less urban development along it. This gives a lot of clear space to work with.

The vision for the Pūharakekenui is to create a riparian river corridor with associated core forest areas. The means a continuous or near continuous belt of riparian vegetation along the whole Pūharakekenui, joining together several large reserves of high ecological value and many small

stands of native trees throughout the catchment. This interconnected ecological zone will support stable populations of birds and invertebrates that can move all throughout the river system to feed and disperse, while spreading pollen and seeds of native plants to make sure those populations are self-sustaining too.

The Pūharakekenui currently has some high value natural assets, such as the Styx Mill Reserve and Te Waoku Kahikatea. The Styx Living Laboratory Trust is heavily involved in projects to develop a high value riparian corridor along the river, undertaking a five year restoration project involving

planting 115,000 riparian plants, controlling 35 hectares of invasive willows, and protecting the riverside with 12 kilometres of stockproof fencing. Planting in the Pūharakekenui uses a diverse mix of species, often from carefully sourced local genetic groups, and incorporates key species such as plants that provide food for birds.

Categories of Riparian Cover:

Impervious: Roads & tarsealed / concreted paths, buildings

Unvegetated: Earth, rocks, gravel

Lawn: Regularly mown mix of grasses and short herbs

Grass & Herb Mix: Unmanaged, short or long

Low Ground Cover: Herbaceous and other low growing plants, such as small garden exotics, and vines such as ivy and nasturtium

Ferns

Rush / Sedge / Tussock

Coarse Vegetation: natives include flax, raupo and toe toe; exotics include lilies and bear’s breeches.

Shrubs: natives include hebes and coprosmas; exotics include broom, gorse, and rhododendron

Trees: natives include cabbage trees, tree ferns, native conifers (kahikatea, matai, totara) and angiosperm trees (kowhai, wine berry, ribbonwood, tree fuchsia); exotics include deciduous trees like willows and poplars, and evergreens like pine, macrocarpa, eucalyptus, and acacia